#4A Strengths and Vulnerabilities of the European Union’s AI Act: Part I

This blog post is divided into two parts. Part I explores the strengths of the EU AI Act, highlighting its ambition to establish a regulatory framework for AI that ensures safety, trust, and ethical compliance. It also examines the Act’s risk-based classification and the obligations placed on AI developers and providers. Part II, which will appear in March, shifts focus to the vulnerabilities and challenges of the EU AI Act, including legal uncertainties, potential regulatory burdens, and its impact on Europe’s AI competitiveness in a fast-moving global landscape. Together, these two parts provide a comprehensive analysis of how the EU AI Act shapes the future of AI regulation, balancing principles of trust and innovation with economic and geopolitical realities.

In June 2024, the European Union (EU) implemented a significant body of regulations on Artificial Intelligence (AI) called the EU AI Act[1]. With great pride, the EU has positioned itself as the first to adopt a comprehensive framework inspired by ethical principles[2] “to ensure better conditions for the development and use of this innovative technology”[3]. But while the purpose is to advance AI innovation and safety, many question whether the Act’s requirements will prove more cumbersome and costly than they’re worth. Defining the right level of regulation on such an impactful technology is a tricky question: too much regulation might refrain from innovation, but too little might lead to mistrust in AI.

In the European Union, on the one hand, the Act is said "to foster innovation" while "ensuring that AI is built in a safe and trustworthy environment," protecting the individuals' health, safety, and fundamental rights. On the other hand, while it creates a regulatory framework to address ethical issues, the Act still reflects many uncertainties that weaken Europe in today’s AI geopolitical race, especially given the fragile nature of Europe’s economic markets and its position in the world.

A regulation expected to set the stage for “Trustworthy AI”

The AI Act essentially comprises two parts: regulating “risky” AI systems on the European market and fostering innovation by supporting regulatory experimentation with AI systems.

Unlike the consensual or voluntary framework developed by the U.S. National Institute for Science and Technology (NIST), compliance with the EU AI Act is mandatory for any operator[4] who, anywhere in the world and interacting with the European market, would consider designing, developing, deploying, importing, providing, or customizing an AI system intended for the EU market.

Consequently, failure of an operator to comply with these obligations can lead to sanctions such as fines or penalties by EU Member state regulators and Courts and even by the European Court of Justice[5]: according to Chapter 12, penalties are scaled depending on the nature of the non-compliance and the nature of the operator. For instance, non-compliance to the prohibited AI system rule (article 5) could be “subject to administrative fines up to 35,000,000 EUR or 7% of its total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher”. Non-compliance to other provisions, such as transparency obligations for providers or deployers, for instance, can be “subject to administrative fines, up to 15,000,000 EUR or 3% of its total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher” (close to the €20 million or 4% of the global annual turnover for non-compliance with GDPR obligations).

What steps should a business take to implement AI systems and adopt digital activities?

The EU AI Act was adopted to “foster responsible artificial intelligence development and deployment in the EU”[6]. The proposal of the European Commission has been the subject of numerous debates as part of the European legislative procedure, allowing the European Commission, the Council of the European Union, and the European Parliament[7] to exchange views, amend drafts, and find compromises until the final vote. Now, with 113 articles, 180 recitals, and 13 annexes, the Act entered into force on August 1, 2024.

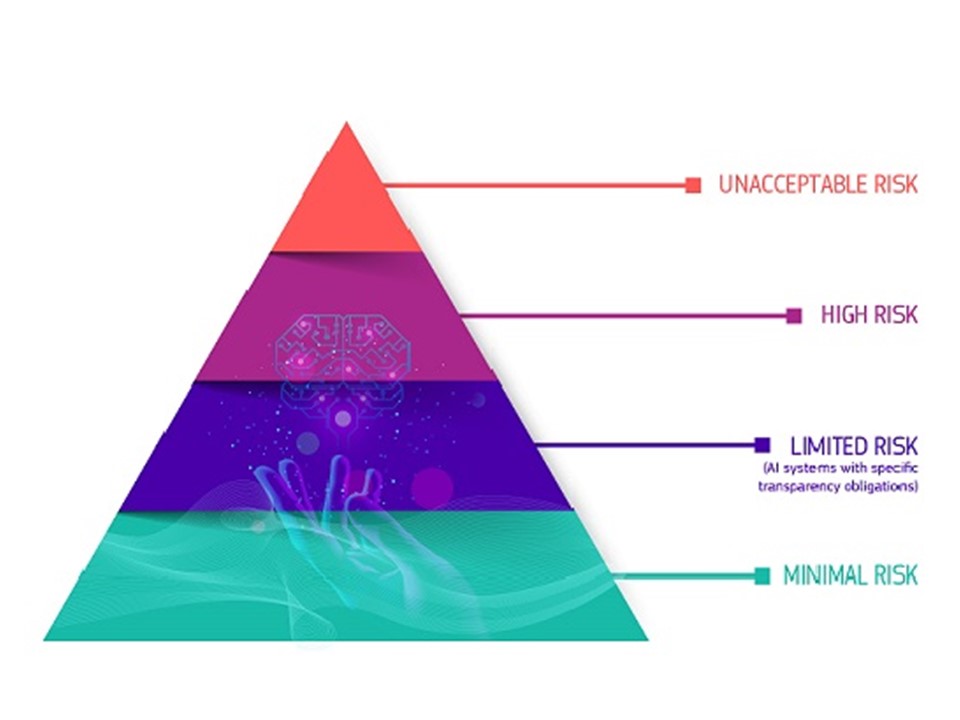

Based on the desire to ensure safety, health, and fundamental individual rights, the main framework is structured as a pyramid of risks: the lower the risk, the fewer legal constraints on the AI system in the EU market; the greater the risk, the heavier the legal obligations with further penalties for non-compliance.

Nota bene: Any operator who wishes to design, develop, deploy, supply, import as an authorized representative, or distribute an AI system on the European Union market must first decide which risk category the chosen AI system belongs to and then comply with the obligations relevant to the risk category. We can reasonably expect some consultancy to bloom in the next few months, suggesting, maybe via an AI tool, which category your AI system fits.

Risk Categories of AI Systems

According to Professors Christakis and Karathanasis, the Act’s risk-category (or risk stratification) approach is based on a model’s level of criticality towards the EU’s core values and fundamental principles as well as the number of models involved. However, it is anticipated that most AI systems will fall under minimal and limited risk categories and, consequently, remain largely unaffected by this Act's sharper regulations.[8]

A risk-based approach: The AI Act defines 4 levels of risk for AI systems

European Commission, Shaping Europe's digital future see https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/policies/regulatory-framework-ai

Prohibited practices

At the top of the risk pyramid is a group of practices deemed so risky that they are prohibited on the European market. If an AI system entails such risks, it should be banned from European soil or punished with penalties or sanctions. Types of prohibited functionalities include:

- Using techniques of sublimation or manipulation on vulnerable persons or groups such as children,

- Classifying individuals for social rating purposes to obtain credits for access to public services,

- Using biometric identification and profiling individuals based on their risk of committing a criminal offense or inferring emotions in workplaces and educational institutions (with exceptions for police reasons or other duly identified reasons)

- Deploying remote, real-time biometric identification systems.

These prohibitions, set out in Article 5, provide for certain exceptions, such as in law enforcement and under specific conditions (in particular, if the control is authorized by judicial warrant and subsequently for reasons of use).

High-risk Category

Less risky in the risk pyramid, the category of high-risk AI systems does not refer to familiar but serious risks involving privacy, bias, discrimination, transparency, or security, as we see it frequently in the US. Instead, it relates to an individual’s safety, health, and fundamental rights (Article 6) since these are the core foundations of the European Union’s esprit. This is the reason why the EU devoted so much time and provisions to this category. In all the following cases, AI is not prohibited, but the EU considers that the risks to individuals'[9] safety, health, or fundamental rights require compliance with specific obligations:

- Firstly, as the European market is partly defined through the European protection of the customers against product liability issues, if the considered AI system acts as a safety component of a product intended to be sold on the European market or as the product itself, then the EU AI act views it as relevant to the “high-risk” category, which requires a certificate of conformity.

- Secondly, high-risk models will include those performing:

- identification and categorization, particularly in biometric or immigration matters,

- Determining access to and eligibility for credit, employment, selective educational programs, social housing, or specific medical treatments.

- Assessment of the solvency of a natural person, pricing of life or health insurance, risks associated with irregular immigration, or insecurity linked to migration.

- Reprimand, punishment, or interpretation of facts in judicial or extra-judicial matters,

- Finally, the influence on an election or referendum in their results, during voting, or in the organization of electoral operations.

These categories will help define the relevant compliance rules. Almost certainly, though, the high-risk classification will not prove easy to apply, and in many cases, the relationship between prohibited and high-risk categories will have to be clarified through the subsequent European Commission guidelines, as mentioned in Article 96.

The legal regime for high-risk AI systems

First, the provider can assert several exceptions before national authorities but must register their AI systems in a national public register. Moreover, if an AI system belongs to the high-risk category, the provider must comply with several obligations relevant to this class throughout the AI lifecycle. The provider must:

- Report technical documentation and show that they archive documentation (Article 18),

- Monitor the risk management process throughout the life cycle of the AI system (Article 9),

- Monitor the quality and good governance of data (Article 10),

- Show proof of an AI system quality management (Article 17),

- Demonstrate specific arrangements to ensure human oversight (Article 14),

- Adopt special requirements involving transparency, robustness, and cybersecurity (Articles 13 and 15).

Before such an AI system is placed on the European market, the operator must then obtain a certificate of conformity through an internal control procedure or from a so-called “notified body,” depending on the specific sector and the types of risks raised by the AI system (Article 43), while the provider must fulfill these obligations, prepare the conformity assessment, and get the certificate of conformity.

Consequently, in addition to classifying risks, obligations, and procedures, the Act also defines the authorities who, at the European or national level, oversee the mechanism of conformity assessment and certificate (Article 44), especially through “notifying authorities” and “notified bodies” (Articles 29-31) with the mechanism.

In this description of the obligations imposed on operators of high-risk AI systems, bodies governed by public or private law exercising a public service mission must also assess the risk of AI infringement of fundamental rights (Article 27) and report on the additional human control system they plan to integrate to ensure that these fundamental human rights will be respected.

Minimal and Limited Risks Categories

If the risk is minimal, as in the case of AI systems contained in recreational video games or spam filters, operators do not have any constraints imposed by EU AI law.

For limited-risk AI systems, including decision-making tools, management software, and data analysis systems, operators must comply with transparency obligations and inform users that an AI system is performing the relevant task (Article 50). Examples might include chatbots, deepfakes, or biometric ID systems that consumers consent to.

An additional category to the risk pyramid: the “systemic risk” for a general-purpose model of AI

As the European Commission proposal was tabled in 2021 before Chat-GPT was displayed and became the Game Changer, the European institutions had to update the text and provide a regulatory mechanism adapted to this new AI model. In so doing, the EU legislator now considers that “this general-purpose AI model may sometimes, especially when its cumulative amounts of computation used for its training … is greater than 1029” be considered with “systemic risk” requiring special procedure and special obligations (articles 51 to 55) and then, falling outside of the previous presentation of the risks’ pyramid.

Thus, the risk description, nature and scope of the obligations, range and amount of the penalties, and the provisions relevant to national and EU levels all indicate the European institutions' willingness to establish an AI approach that fits into the values and choices defined by the European Union. Human oversight of the entire AI system is prioritized and reflected in a constraining and complex legal framework. These regulations to ensure the security and trustworthiness of AI systems are then considered crucial in the European Union.

To what extent will they allow some reasonable space for freedom, innovation, and dreams about AI's capacity to transform our world?

Author

— by Anne-Elisabeth Courrier, PhD, Associate Professor in Public Law, School of Law and Political Sciences, Nantes Université, France, and AI Ethics Liaison, Emory Center for Ethics, Adjunct, Emory Law School, Emory University, 2/2025

Anne-Elisabeth Courrier, PhD, is a visiting Professor at Emory University in Atlanta, an Associate Professor in Comparative Law at Nantes University (France) and AI Ethics Liaison at the Emory Center for Ethics from January 2025. Focusing on Law and Ethics on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Data, she created a program called "Simuvaction on AI" for international students. She launched the online educative program "The Ethical Path to AI: Navigating Strategies for Innovation and Integrity | Emory Continuing Education" (27 January 2025) to help professionals with tools and ways to handle ethical questions about AI. In June 2022, she was recognized as "Knight of the Academic Palms" by the French Government.

_______________________

[1] The EU AI Act, Regulation EU 2024/1689 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 laying down harmonized rules on artificial intelligence and amending Regulations, see https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32024R1689– For more information about the text, see https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/qanda_21_1683 and European approach to artificial intelligence | Shaping Europe’s digital future

[2] High-Level Group of Expertise of the European Union, (2019)., Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai

[3] European Parliament, (2023.), EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence, The use of artificial intelligence, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/topics/en/article/20230601STO93804/eu-ai-act-first-regulation-on-artificial-intelligence.

[4] According to Article 3 (8), EU AI Act, “an operator means a provider, product manufacturer, deployer, authorized representative, importer or distributor”

[5] According to Chapter 12, penalties are scaled depending on a combination between the nature of the non-compliance and the nature of the operator: for instance, non-compliance to the prohibited AI system could be “subject to administrative fines up to 35 000 000 EUR or 7% of its total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher. Non-compliance to other provisions such as transparency obligations for providers or deployers, or to the series of obligations defined for providers, importers, distributors can be subject of administrative fines up to 15 000 000 EUR or 3% of of its total worldwide annual turnover for the preceding financial year, whichever is higher

[6] European Commission, the EU AI enters into force, August 2024, AI Act enters into force - European Commission

[7] The European Council (bringing together Heads of State or Government), which is not strictly part of the legislative process, has taken the initiative to intervene and give impetus to the text.

[8] Christakis (T)., Karathanasis (T)., Articles, "Tools for navigating the EU AI Act: Visualization pyramid, March 7, 2024, Tools for Navigating the EU AI Act: (2) Visualisation Pyramid - MIAI

[9] As reflected in the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

Continue the conversation! Please email us your comments to post on this blog. Enter the blog post # in your email Subject.