#4B Strengths and Vulnerabilities of the European Union’s AI Act: Part II

This is the second part of a blog entry on the “Strengths and vulnerabilities of the European Union’s AI Act”

Part I explores the strengths of the EU AI Act, highlighting its ambition to establish a regulatory framework for AI that ensures safety, trust, and ethical compliance. It also examines the Act’s risk-based classification and the obligations placed on AI developers and providers. Part II, shifts focus to the vulnerabilities and challenges of the EU AI Act, including legal uncertainties, potential regulatory burdens, and its impact on Europe’s AI competitiveness in a fast-moving global landscape. Together, these two parts provide a comprehensive analysis of how the EU AI Act shapes the future of AI regulation, balancing principles of trust and innovation with economic and geopolitical realities.

Intended to address the ethical challenges raised by AI use and ensure that AI systems align with the European system of values, the EU AI Act is designed to establish trustworthy AI models and, consequently, shape commercial and industrial products and services into a reliable human-machine interaction. This ambition is obviously noble, but legal and institutional uncertainties and pressure from the internal, European, and global AI race put those good intentions at risk.

Uncertainties from the very EU AI Act

The implementation of the Act is marked by numerous uncertainties, most of them related to its expedited rollout. First of all, while the "AI system" is broadly defined in Article 3(1)[1] the very definition of "artificial intelligence"—referring to practice, examples, and use cases — is still under discussion: on December 11, 2024, the European Commission initiated a consultation to help set guidelines for the interpretation of the AI definition.[2] Furthermore, according to Article 96, the European Commission still needs to define the guidelines on high-risk AI systems requirements, prohibited practices, and the scope of the transparency obligation.

Hyper-regulation of the AI governance

The EU AI Act dedicates a whole chapter to the AI governance organizations at the European level:

- an "AI office”, which, as part of the European Commission, represents “the Union’s expertise and capabilities in the field of AI” (Article 64),

- a European AI Board with representatives of the Member States (Article 65) whose tasks are to ensure coordination among national competent authorities, to issue recommendations on further codes of conduct, codes of practices, Commission’s guidelines, technical specifications, harmonized standards, and “trends, such as global competitiveness in AI, the uptake of AI in the Union and the development of digital skills.” (Article 66).

- an advisory forum designed to “provide technical expertise and advise the Board and the Commission” (Article 67).

- and a “scientific panel of independent experts, selected by the Commission for their expertise and independence (Article 68).

In addition to this European AI governance design, in enforcing activities under this regulation, “Member States may call upon their own pool of experts (article 69), designate their national competent authorities and single points of contact.

Why refer to so many EU and national AI governance chains?

Are there questions in Europe about believing in the actual capacity of building a “trustworthy AI” or in the positive implications of AI on our society? Beyond sporadic cases of AI's social acceptability, Europe has shown tremendous enthusiasm for AI and its potential to transform society.

Instead, the inclination for hyper-regulation of AI governance might reflect a feature of the “unfinished History of the EU.” Indeed, when the European treaties were designed in the 1950s, their institutional governance was based on a four-pillar structure: the Commission representing the Union’s interests, the European Parliament representing the Peoples, the Council of the European Union representing the Member States, and the European Court of Justice representing the EU Law. In 2005, the “European Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe” had the ambition to transform the European economic perspective into a political project of a constitutional federation. However, this treaty was not adopted, precluding full European integration and pushing back the European Union into political competition for influence between Member States, the Council of the European Union, and the Commission, with conflicts ruled out by the European Court of Justice. Hence, it requires much more time, effort, and negotiations to ambition beyond consumer protection, the implementation of a unique European whole tax policy, or a unique European entire capital market, which would be pretty much needed to create big AI unicorns.

Today, the regulation of European AI governance into complex administrative layers, bodies, tasks, and reasonings demonstrates that beyond the vision of a “trustworthy AI” for Europe, the potential of AI economic growth is such that the European Commission and the Member States (not to mention the role that awaits the European Court of Justice) are vying for influence, showing finally, how much AI is not only an economic variable but also a matter of political power.

Uncertainties related to controlled innovation

The European Union wants to bet on AI's economic potential and considers the EU AI Act, as an opportunity to strengthen innovation. Therefore, alongside the legal framework to ensure safe and trustworthy AI, "innovation support measures" will be put in place through two flagship measures: 1) the real-time testing of high-risk AI systems and 2) “regulatory sandboxes” set to launch on August 2, 2026. However, in the EU’s regulatory culture, strengthening innovation will require institutional and public support for governance, paired with distinctive characteristics of Europe in entrepreneurship culture, risk management, and speed of institutional support organized in a fragmented market.

Real-time testing of high-risk AI systems

Real-time testing of high-risk AI systems is already permitted under the EU AI Act. However, the market surveillance authority of the Member State must approve a "testing plan" prepared by the provider that spans no more than six months. The testing plan must include the informed consent of the trial participants, commitment to prompt notification, and liability assumption for any damage, which will be automatically borne by the provider (Article 60). Importantly, these requirements apply exclusively to high-risk AI systems, but governmental involvement remains significant, so it remains uncertain as to whether governmental regulations might slow down rather than strengthen innovation in Europe.

Regulatory Sandboxes

"Regulatory sandboxes" are designed as physical and/or digital "controlled environments" (Article 57(5)). They must be opened by Member States — at least one per State from August 2, 2026 — with the aim of fostering “innovation and competitiveness" (Article 57 (9) (c)). The goal is to ensure compliance with European regulations when products and services are placed on the market.

These measures, however, will be under the control of the European Commission and national authorities. They will be responsible for setting the conditions for application, operation, and supervision by “implementing acts”[3] through "guidelines on regulatory expectations and how to meet the requirements and obligations set out in the next regulation" (Article 57).

The compliance costs of these requirements and the current expenses of uncertainties do not seem to be contemplated in the Act, which might incline some businesses and start-ups to leave the European Member States. Companies might wish to move innovation hubs abroad, perhaps on American soil or elsewhere, to be free to experiment and then, in a second stage, learn how to comply with European regulations.

Uncertainties related to Internal competitions in Europe

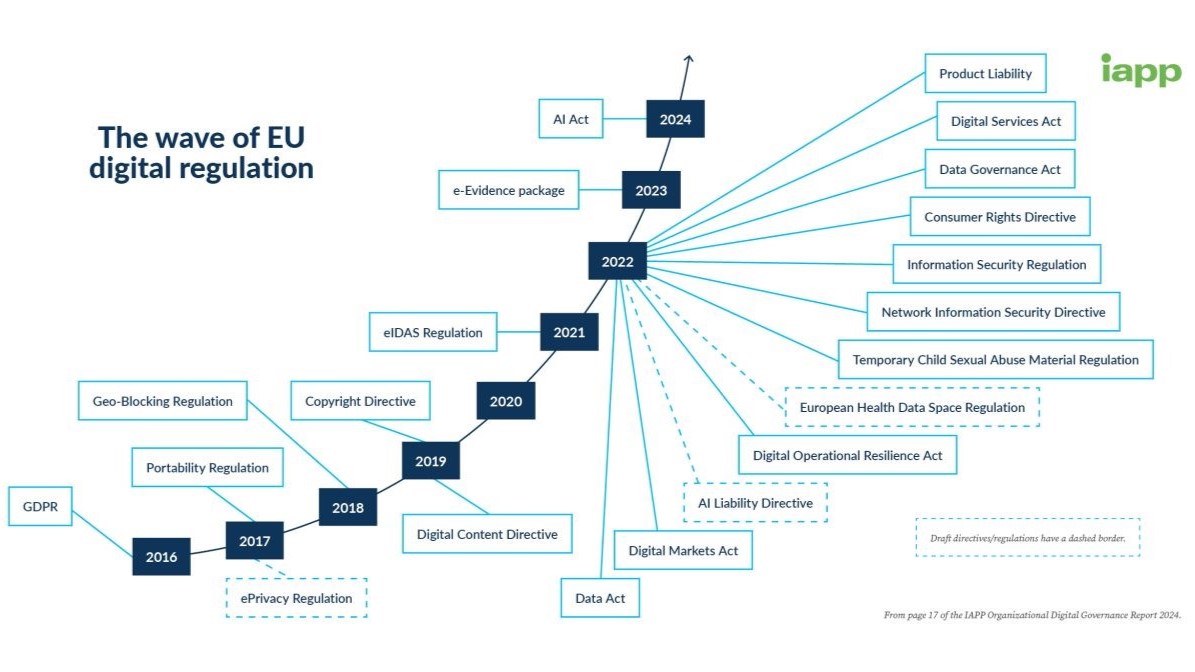

The adoption of the EU AI Act comes amidst what the International Association of Privacy Professionals calls the "wave of European digital regulation," populated by laws like the General Data Protection Regulation, the Digital Market Act, the Digital Service Act, the Data Governance Act, and the directive on product liability. This slew of regulatory requirements will almost certainly ensure the prosperity of Europe’s legal professionals.

IAPP, Digitalized Governance Report 2024, p. 17.

The dynamic among regulatory entities will result in a dense and ongoing conversation between algorithmic experts within the European Union and the EU’s national authorities. For instance, in addition to the EU AI Act, the European Parliament has developed a series of resolutions on AI use and ethical challenges[4]. These resolutions have no significant legal scope, but they have provided a way for the Members of the European Parliament to share their positions and participate in expanding the number of requirements adopted by Member states.[5] That conversation will undoubtedly be complex and doubtlessly witness a host of not-always-aligned values and goals.

EU Institutions and Council of Europe

The Council of Europe, established in 1950 as an international organization to ensure democracy and human rights all over Europe and gathering 46 Member States in Europe, is also trying to raise its voice and influence how Member States must ensure that AI does not endanger human rights.[6] On May 17, 2024, the Committee on Artificial Intelligence of the Council of Europe adopted a “Framework Convention on AI and Human Rights, Democracy, and the Rule of Law”. This text suggests its own definition of “artificial intelligence” with the same concepts but in a different wording. It defines objectives to be applied by each Member State, with a general purpose of maintaining or taking all necessary measures to “adopt or maintain AI systems consistent with human rights, democracy and the rule of law.”[7] It strongly advises the Member States to adopt risk assessments and management processes aligned with its principles (as reasserted in the convention). It also dedicates one of its chapters to “remedies.” Throughout history, we have seen that the European Court of Human Rights case law, as part of the Council of Europe, has developed its autonomy in vocabulary, proceedings, reasonings, and judicial policies as different from those of the European Court of Justice (as part of the European Union). That difference might also hamper the implementation of the new Convention Framework.

Economic impact

The normative preoccupations of the European Union, whose regulations are in competition with those of the Council of Europe's new Convention, have created a regulatory environment whose economic impact might result in severe liability. Published on September 9, 2024, the Draghi Report, named "The Future of European Competitiveness,"[8] lamented that “we are failing to translate innovation into commercialization, and innovative companies that want to scale up in Europe are hindered at every stage by inconsistent and restrictive regulations….Between 2008 and 2021, close to 30% of the "unicorns" founded in Europe – startups that went on to be valued at over USD 1 billion – relocated their headquarters abroad, with the vast majority moving to the US...[9] We claim to favor innovation, but we continue to add regulatory burdens onto European companies, which are especially costly for SMEs and self-defeating for those in the digital sectors."[10]

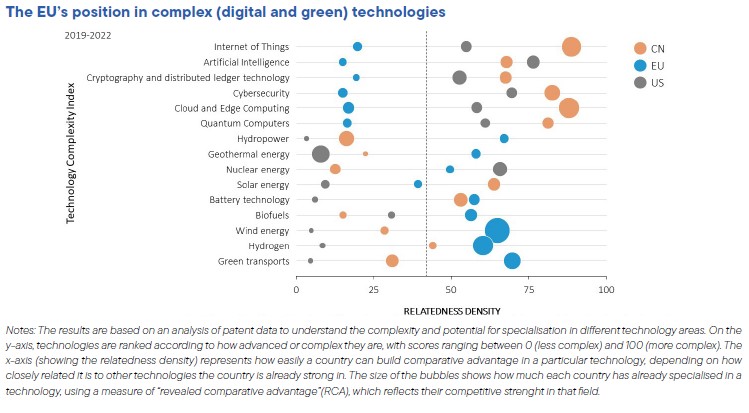

The graphic below illustrates the EU’s position in complex technologies: although the EU has developed a leadership role in green technologies, its position in AI, the Internet of Things, cryptography, cybersecurity, and quantum computers is relatively backward.

Report Draghi, "The Future of European Competitiveness," September 9, 2024, p. 36.

EU AI Act and geopolitics

When the EU AI Act was passed, the European Commission quickly noted that it was the "world's first comprehensive regulation on artificial intelligence."[11] In fact, it seeks to replicate the international success achieved under the GDPR: Under the GDPR, the EU only allowed the transfer of data to a third country on condition that the requirements of a high or at least equivalent level of data protection could be guaranteed in that third country[12]. This tactic has led some states to enhance their own personal data protection policies, and thanks to the multiplication of these bilateral agreements on a global scale, it has succeeded in ensuring that the European data protection position is one of worldwide reference[13].

Building on such success, the EU aims to replicate this influence on third-party countries’ AI development strategies, hoping to become a reference legislation in a disparate international landscape. However, given AI's potential for economic development, the United States of America is relatively reluctant to adopt regulations that would risk slowing down innovation. While the US considers AI development first a matter of technological competition, economics, and geopolitics, the EU has shown its desire to align AI policies with its values despite the burden of excess and stacking of regulations.

To conclude, beyond the details of these regulations and their intent to foster innovation, European policies on AI are set to be loyal to values and ideals and show a strong readiness to impose a culture of legal AI through space and time, although it might refrain from some economic opportunities and technological innovation. The European focus on regulation was so dense, despite its costs in time and money, that one can wonder if AI ethics could have been conceived through other means, such as technological advancements or mandatory education on these issues.

There should be another way, perhaps consisting of four parts: The first makes room for innovation without immediate governmental control, but such innovation nevertheless occurs in the midst of 2) a universal agreement on a defined set of human rights protections along with 3) clear liability rules for the various roles attached to the use of AI, now regulated by the judicial and quasi-judicial systems and 4) compulsory education to develop awareness and identification of ethical questions raised by AI. Especially important is how these clarifications might enable developers to position themselves on the type of uses in a duly identified risk context without needing constant recourse to legal rulings.

_______________________

[1] According to Article 3(1), an "AI system" is "an automated system that is designed to operate at different levels of autonomy and can demonstrate adaptability after deployment, and which, for explicit or implicit purposes, deduces, from the inputs it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations or decisions that may influence physical or virtual environments";

[2] See, European Commission, Commission launches consultation on AI Act prohibitions and AI system definition, November 13, 2024,

[3] Article 58

[4] Here are some of the Resolutions adopted by the European Parliament on digital matters: Artificial Intelligence in a Digital Age (2020/2266(INI)), May 3, 2022; European Data Governance (2020/0767(INL)), December,15, 202; Digitising European Industry, June 1, 2017; Towards a Thriving Data-Driven Economy, March 10, 2016; Comprehensive European Industrial Policy on Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, February 12, 2019.

[5] In addition to the texts adopted by the institutions of the Member States.

[6] On AI policy as much as on other topics, see the debates on the supra-constitutionality of European texts or on the precedence of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights over the European Convention of Human Rights and the dialogue between the two European Courts of Justice, respectively.

[7] Article 1 of the Council of Europe Framework Convention on AI, Human Rights, Democracy and the Rule of Law. See https://rm.coe.int/1680afae3c

[8] Report Draghi, The future of European Competitiveness", September 9, 2024

[9] Id. p 3.

[10] Id. p 4.

[11] European Commission, Press Release, July 31, 2024 – see https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_4123

[12]New Standard Contractual Clauses - Questions and Answers overview - European Commission

[13] This position was painfully achieved between the EU and the United States, notably through the known setbacks on data sharing via the Privacy Shield and the Safe Harbor, both of which were annulled by the "Schrems" rulings of the European Court of Justice.

Author

— by Anne-Elisabeth Courrier, PhD, Associate Professor in Public Law, School of Law and Political Sciences, Nantes Université, France, and AI Ethics Liaison, Emory Center for Ethics, Adjunct, Emory Law School, Emory University, 2/2025

Anne-Elisabeth Courrier, PhD, is a visiting Professor at Emory University in Atlanta, an Associate Professor in Comparative Law at Nantes University (France) and AI Ethics Liaison at the Emory Center for Ethics from January 2025. Focusing on Law and Ethics on Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Data, she created a program called "Simuvaction on AI" for international students. She launched the online educative program "The Ethical Path to AI: Navigating Strategies for Innovation and Integrity | Emory Continuing Education" (27 January 2025) to help professionals with tools and ways to handle ethical questions about AI. In June 2022, she was recognized as "Knight of the Academic Palms" by the French Government.

Continue the conversation! Please email us your comments to post on this blog. Enter the blog post # in your email Subject.